Thanks to Cart Boy for edits.

The pitch is incredible. You’re a 19th Century insurance adjustor for the East India Company. A ship, the Obra Dinn, has suddenly found its way back to the English coastline after having been lost at sea for five years. It’s a ghost ship; anyone who somehow survived it was wise enough to make tracks some time ago. But for an insurer, that’s not enough. What actually gets paid out to the estates of each victim or survivor, if anything, is dependent on the trauma that person experienced. And that’s where you come in, figuring out the fates of the sixty people unfortunate enough to have made the passenger manifest. Each heroic sacrifice, cruel betrayal, shocking escape, and act of hubris is just one more thing to record.

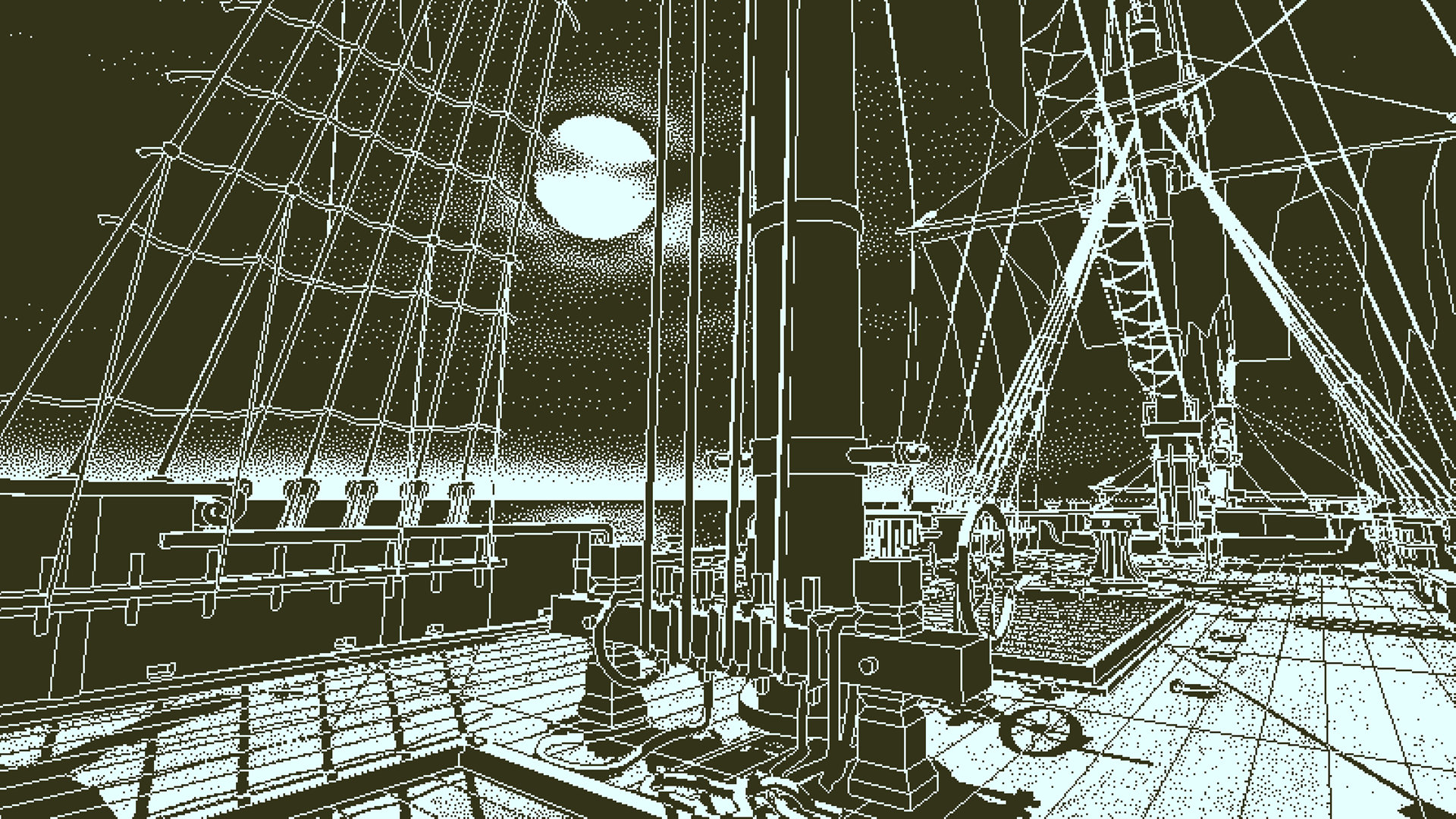

I love telling people this premise. For non-players, it shows how weird and imaginative this industry can be. For players, especially ones like me who love a good mystery, it claims an impeccable gameplay hook. Return of the Obra Dinn, Lucas Pope’s scintillating follow-up to Papers, Please (whose hook, “what if you were an impoverished border patrol guard of a brutal Soviet bloc state,” was wild in its own way), is kind of intoxicating at first glance. From its story to its intense, monochrome visuals, it feels fundamentally unique. Of course, it’s not wholly out there. The graphics are a direct homage to binary image graphics in old Mac computer games; they’re just far more complex and dynamic when creating an HD, 3D world. And like many mystery games, it has its own gameplay hook: seeing each death just as it happens.

This comes through the game’s main mechanic, and the only other thing I like to mention in those summaries: the Memento Mortum. It’s a pocket watch that, when near any corpse, can turn back time to the unmovable moment of a person’s death. There’s no animation of the scene – a technical limitation of one of Pope’s early gameplay tests that ultimately led to a more interesting work – though you do get the last few seconds of sound the person heard. Ostensibly, being there right as it happened there should make things clear; if a person was shot, you should be able to see the bullet, the trail, the gun, and the shooter. And the dialogue should be able to help even further, letting you hear names and context.

In practice, though, Return of the Obra Dinn works around the clock diligently to make that perspective just as obscuring as it is revealing. Part of that comes from the next brilliant element, which is how you actually write down these deaths. You have to identify every person you find, how they died (if they died, which is unsurprisingly the case for most of them), and, if applicable, by whom or what. If you see, for instance, a memory of a man being stabbed with a sword, you can put the “killed (sword)” explanation as his fate, but it’ll immediately offer a space to put in his killer. This process forces you to usually start with the face, then the method, and ultimately end with a name. That entirely flips how typical mystery stories are structured, which start you out with at least an identified corpse.

Of course, there’s another wrinkle in that you have no idea who each person is. The ship was last seen in 1802; there’s no photography to check. The closest substitute is a page filled with sketches of the crew in mostly safer times, drawn by the resident artist. The drawings come in a book called Return of the Obra Dinn: A Catalogue of Adventure and Tragedy; the broader plot is that you’re using that to fill out the investigation. When you see a person in a memory, the game matches them to their corresponding place in one of the sketches. And their profile will keep a record of every death in which they were present, complete with diagrams of their movement across the story. This is invaluable for figuring out the nature or histories of these people before you’ve ever identified them. But they still don’t come with names, only clues.

The middle section of the page of sketches. Facial details, positions; all of it can potentially matter.

Of course, the same issues apply to using the spoken word. The folks killed by a shipmate’s hand rarely call out their attackers, though the game is generous enough to mark the victims’ dialogue in their own memories. Several of the easiest vocal clues tend to have less immediate application; in one case, a man you’ve identified describes someone as his steward, but the steward has minimal involvement in most of the story. Often, they’re less about figuring out who someone is than whittling down who they aren’t. This especially comes in the game’s extensive non-English dialogue – the crew of the Obra Dinn is realistically international, and crew members often speak in their native languages – which can narrow down your suspect list.

Cause is also a problem, if to a lesser extent (it’s usually the first thing you can identify). Really, most of the deaths are fairly clear: shootings, stabbings, bludgeonings. But that’s not always the case. Sometimes, a person’s death comes at some point after being dealt a fatal blow, not immediately. Sometimes, the scene is deliberately confusing. Return does allow a few deaths to be correctly recorded in a couple ways, but you still have to study the scene fairly aggressively.

And there’s the rub, where the true brilliance – and pain – of Return of the Obra Dinn is on full display. The only way you can figure out every fate and name is by studying each scene as a whole, not just the morbid money shot. You have to start focusing less on the moment itself and thinking of the memory as a resource to be stripped for parts, and not just for identifying that particular victim. And that’s because, more often than not, the clues they have are more for identifying totally different people than the stiff at their center. Some of these clues will be important for deaths that happened at the same time, and some will be important for deaths at the opposite end of the plot. Any kind of significant linear progression is essentially impossible beyond finding a few successive deaths, which is good since strict linearity often worsens mysteries anyway.

These three men did not die in this scene. They have no connection to the person who did die. But perhaps by seeing how they interact at this point, you can better understand them.

That’s an odd but necessary mechanic in its own right. It would not be a spoiler to say that most of the bodies were lost at sea at some point, so finding a way to see their deaths would be impossible normally. This would make the game both effectively impossible and not nearly as narratively satisfying, so the Momento Mortum lets you sort of… chain deaths together. If you find a corpse in another memory that disappeared some point before you stepped aboard, the game will essentially recreate it on the ship for you to explore. Most of the last memories you identify tend to come from this process. However, this only extends to people who died on either the Obra Dinn or one of its lifeboats, and identifying the fate of those who either survived or died offship tend to be the toughest puzzles in the game.

With all of these complications and tools, the investigation demands an increasingly – at times, absurdly – thorough search. If there’s dialogue, study everything from implied relationships to purely vocal accents to other languages. If a person shows up in multiple memories, study their clothing and posture, and if they’re often in proximity to someone else. Check every number you can see. Check every room they’re in. Check their clothes. See if you can cut down the options of people from the same country or the same rank. Even check that page of sketches, whose subjects often organized themselves based on position or heritage. And other than the art, every clue comes from those creepy, unmoving portraits of death. You have to explore each sequence, often multiple times for multiple reasons. You have to learn to just ignore the actual murder (or accident, or act of god) taking place to focus on what random crew members are doing in the background. And honestly, it can be very helpful to just pull out an actual pen and paper and start writing down details instead of jumping back into memories.

Some of these perhaps go beyond what can reasonably be expected of a player. If your ear for accents isn’t good, or if you have a hearing impairment, you’ll have a problem figuring out several crew members. The same goes for anyone who can’t identify languages that don’t use the Latin alphabet. One character’s identity can best be deduced by knowing the history of French maritime uniforms. And that beautiful art style can be somewhat inscrutable and hard to discern. I’ll confess that I used online guides whenever I got too stuck (which was often), though I did explore the game to find each of the clues I had missed in each case.

A player could, for instance, be forgiven for struggling to get the most out of the cross-section of the boat, which records each memory a specific person was in and how they temporally connect. It’s hard to grasp, but there’s clues just in seeing how people lived on the ship.

There are, however, things that Return of the Obra Dinn does in the interest of accessibility. For one thing, befitting a game about filling out a book, it nicely chops itself into relatively clean chapters. Each chapter is about one main theme, every death you find is written out as one page, and every one of those deaths is tied into that theme (you don’t have anyone dying of old age during a mutiny, for instance). It makes things cleaner, and it creates a stronger sense of theme, but it also makes it much easier to write out the increasingly demented and horrifying drama. And that ease itself becomes, at times, a clue.

The other is from a simple bit of fact checking. Every time you correctly write down three fates – that is, who, how, and from what – they are permanently written into the book and unalterable. The next time you want to put a name to a John Doe, the list will be just a bit smaller. There’s a visual component to this, since the printed word looks more professional than the scratchy notetaking you normally do, but more to the point, it’s incredibly helpful. It prevents you from going too far into theorizing, and it allows you to use guesswork as a tool. Obra Dinn is theoretically able to be played without making a single guess, but if you have some names you know are right and some you think are right, you can exploit that. That’s how I got Winston Smith and Marcus Gibbs, the Carpenter and Carpenter’s Mate. I figured out two people who had to be them, I tried two guesses, and the second one worked.

It is worth mentioning that this – watching deaths, looking for earlier deaths, and writing them down – aren’t the main mechanics of Return of the Obra Dinn. They’re the only mechanics. Combined with the very limited animation (the only movement comes with you on this creaking, dead ship), and you get an incredible and at times very scary world. It’s oddly very ominous; you almost expect some… thing to break free, even though the game is open about its structure and the location is so clearly bereft of life. Everything is stripped down into a quest for knowledge that the game both fights and indulges.

Jump back, look, and write. It’s a rather simple process in a physical sense – just not in practice.

And it’s that relationship that’s led Return of the Obra Dinn to being one of the best mysteries I’ve experienced in years on top of being a brilliant bit of game design. The game’s main idea is to turn the utter opposite of a classic whodunnit – literally giving you the moment of death – and making that itself the challenge. There’s nothing but the most bare bones puzzle solving, but it feels so much greater than that. Pope calls his game “An Insurance Adventure with Minimal Colour,” which reads like a genuinely funny joke but is also completely correct. It has nothing but the methods to solve the mystery, and that makes it so much more.

- Gun Metal Gaming Chapter 4: Bald Whitem’n and the Case of the Missing Franchise - April 30, 2024

- Treasure Collected: The Social Satire of Pikmin - April 24, 2024

- Indie World April 17, 2024: Information and Reactions - April 17, 2024