Dredge, an indie game from earlier this year, has one of those wonderfully charming indie game premises. You’re a fisher off the coast of some far off, late 1920s island chain, and alongside trawling for sharks and crabs, you’re evading the Eldritch horrors of the deep. As day turns to night, your sanity begins to erode, the sea life grows unearthly, creatures attack, the onset fog hides sharp cliffs, and you have to decide whether to keep braving the seas or rest up at a port that may be too far away. Of course, you can’t only operate in the daytime. Plenty of fish and quests can only be dealt with at night, and most islands are so far away that it’ll probably take a whole day to get there. Like most horror or management games, it’s about figuring out what you can and need to do, though it’s a lot more lax than most entries in either genre.

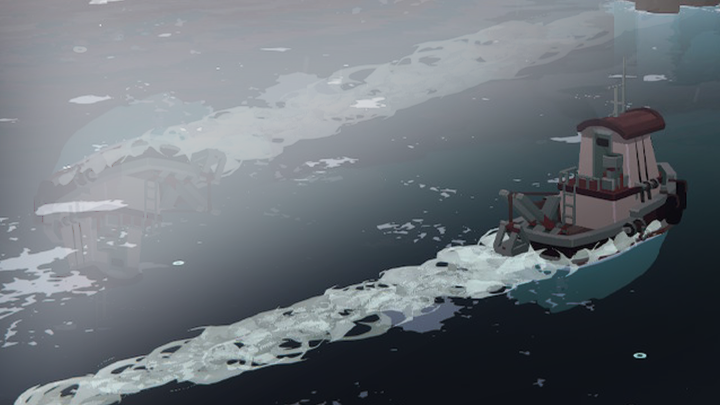

Stylistically, it’s impeccable. The rough character art, polygonal graphics, and fantastic audio work together to create a world that’s harsh and beautiful. Admittedly, the writing isn’t anything special and I suppose the same is true of the plot, this quest to find five cursed artifacts across as many aquatic biomes. It’s all a collection of motley, cursed locals all turning mad, the kind of thing you expect from Lovecraft riffs. But it still works. The game has a wonderful sense of place, and that extends to the actual gameplay.

Image: Source Gaming. The boat being attacked by “something” from the deep.

You never see your character in Dredge, and you don’t need to. The actual playable “character” is their vehicle: an ugly, miserable little boat that holds your every tool and ability. It’s your lifeline, your home, and at times even a bugbear. See, everything you can do is based on the conditions of the boat. If it’s broken, you can barely pilot it. If you haven’t properly organized its contents, you’ll be wasting precious space. If you don’t master its surprisingly smooth tank controls, you’ll be adrift—literally. And that’s what makes the game so great; every aspect of the gameplay is lashed to the ship.

Let me describe a typical in-game day of Dredge. After resting at Gale Cliffs’ port of Ingfell, you leave at 6:00 AM. Your self-given goals are to just catch some fish and maybe a bit of sunken treasure, nothing fancy. You can sell them off—the fish to a local fishmonger, the treasure to an appraiser in Little Marrow—or store them for later, though the fish will eventually rot. Almost everything you find is in a spot on the water; all you need to do is play a quick mini-game, then organize whatever you’ve found in your storage. But every act of fishing or dredging makes the hours fly by, especially if you mess up. Soon it’s nightfall, and things have changed. The fog has rolled in and covered the jagged rocks. Things are starting to appear, like assaultive sea creatures or flocks of birds that steal your catch. Maybe you move too carefully and get attacked. Maybe you move too fast and crash on a rock. But the result is the same: your hull has been breached. One or more of your tiles have been X’d out, meaning you can’t place anything there, whatever disposable item was there has been lost, and if the X is over your engine or rod or light, you can’t use those either. So you try to meekly make your way back, sell your produce or fix your mistakes, and rest up for the next night.

The fun of Dredge is there, out at sea, where you’re constantly deciding what level of threat is acceptable and invariably going past it. But the threat, and the reward, is all tied to the vessel you’re using in the first place. Your speed? That’s based on what engines you’ve installed. Same goes with the rods, which dictate what you can catch and how quickly. And those occupy the same room as whatever you’ve hauled aboard, be it sea life or debris from another ship or quest-important items. Everything you do impacts the boat. Your mistakes are the hull breaches, your successes the bounty, and making it all fit together is a small puzzle.

Image: Source Gaming. The boat’s hull has only suffered one tile of damage, but that space is completely useless until you get it fixed. If something was occupying that space when it was broken, it was knocked overboard.

The inventory management is right out of Resident Evil 4, which turned something dull into an engaging mini-game in its own right. But in a way, this goes even further. Leon’s attache case was always this goofy, abstract thing; he never actually carried it in the game. But the inventory in Dredge is literally the actual boat. Its weird oval shape reflects the frame. The better engines, rods, traps, nets, and lights all take up more space to compensate, except they’re also all limited to space reserved for them. Upgrades you can make to the boat have a more direct impact, because you can literally see each extra space stretch your storage to its limit.

You need these upgrades because that’s the only practical way of escaping the islands at the center and exploring the ocean, where danger and treasure await. However, the game also seeds them in a way that forces you to push the vehicle more and more. You get more space, including more space for your tools, by purchasing upgrades with both money and debris pulled from wreckages. But unlocking the better engines or rods that improve your efficiency needs special items that mostly come from quests. To get these Research Points, you need to push yourself further into rough waters. The reason why Dredge is more generous than most horror games is that you have control over when you descend into the danger, but you still have to at some point. Maybe a quest demands a fish that only comes out at night—or a haunted, Lovecraftian counterpart covered with eyes or fangs. Maybe the distance between where you are and where you need to be is too long for a daytime excursion.

Image: Source Gaming. Dredge‘s lighting and art direction craft this sense of mystery and unease. It makes your boat feel as puny as it is.

And you feel it at every moment. The way each engine lets you move faster but is just a bit harder to control at top speed. The harsh wind that pushes your boat ever closer into a cliff. The way every slash in your hull shakes the screen. The dynamic changes in lighting as you fall into a mangrove or out of your mind. The calm from staying still and checking the map, but also the fear, because since time only passes when you’re actively doing something, the only way to escape the nightmare is to keep moving. But there are empowering feelings, too, like the strength of your upgraded engines or the satisfaction at bringing home so great a number of fish that your ship is close to bursting.

It’s a triumph of game feel, and a great example of how the sensation of playing a game goes hand in hand with that game’s mechanics. Every aspect of Dredge is inexorably tied with each other. The stress of taking damage or learning that “something” has slithered onboard and is infecting your cargo is intense, but it’d mean a lot less without the stress of also having to drive between rocks, sandbars, and destroyed temples just to get to a safe dock. The puzzles based around carrying explosives to open pathways are fun because you’re debating exactly what you need and want to do while you’re doing it. As it was in Resident Evil 4, trying to obsessively sort everything together has a fun, addicting quality—especially since the way you sort your gear has a material effect. You never feel apart from the boat.

This aspect of game design is hard to easily quantify. You can point to a map to show nonlinearity or a boss’s stats to show combat mechanics, but that idea of game feel is so much more nebulous. And yet, that’s why it’s so exciting. It makes you feel something that no other medium in the world can make you feel. It’s also not magic; all those mechanics work together to instill that. Dredge is great for a lot of reasons, but the way everything works back around to make you feel weak, scared, and empowered is the best one.

- Treasure Collected: The Social Satire of Pikmin - April 24, 2024

- Indie World April 17, 2024: Information and Reactions - April 17, 2024

- Gun Metal Gaming Chapter 3: Second Acts in Gaming Lives - March 30, 2024