It starts with one square, and then, a fin. Then it zooms to the child. We try to see what the fin is: a fish, a coral, no…a dragon, moving through the city streets. Then we see the orbs in a bowl and from them, the city with the fin once again, behind a window. A moment later, the fin is gone. The one square becomes two, there’s a second boy – himself in a wheelchair – and eventually, those squares slowly come together again. Time and space fold into each other, communicating and turning backwards and forwards under a sea of ephemera. But the orbs, the boy, and the fin and eye of the monster are always there.

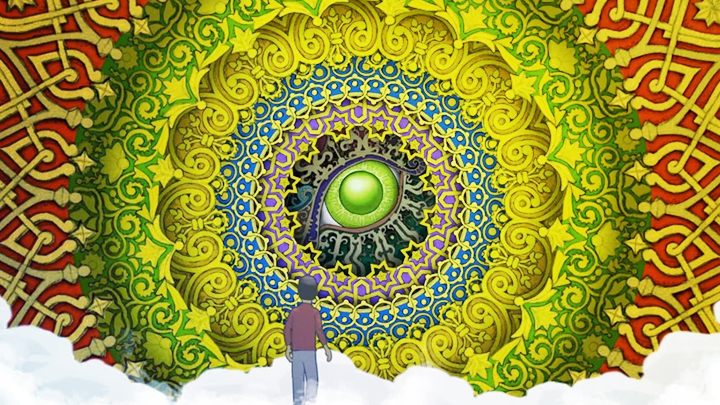

Promotional screenshot for the game, though I believe this is a collage of several scenes.

It’s hard for me to really describe exactly what it is you do in Gorogoa, Jason Roberts’ brilliant 2017 puzzle game, through writing, despite the fact that it’s rather simple in practice. Okay, so the entire game takes place in a large square, partitioned into four smaller squares. While it’s rare for all four to be used at once, each panel can hold a separate image. These images show wildly different scenes (or wildly different depictions of the same scene), and for the most part you can grab and stick each panel in whichever position you’d like and swap it with whatever’s already there. However, pictures set in even wildly disparate spaces or worlds can be visually connected; what might seem like detritus in one picture’s left edge (like a rope or part of a wall) will fit in perfectly in another picture’s right. From there, the goal is to then get at least two of the squares to match into a single image that kicks off a short visual story, orbiting around a young boy’s quest to find five colored orbs. Finishing each sequence leads to the next step of the game and with it, additional puzzles. Beyond the interconnected story, what separates this from any conventional tile puzzle is that each image is itself interactive; you can zoom in and out in specific ways, allowing the image in the square to take on a whole new meaning. And thus, you have to explore up to four separate worlds within the squares themselves to find the various orbs.

From the Wikipedia page; it’s easier to show through visual aids.

This sounds intimidating, and some puzzles – especially those near the end – are fiendishly clever and difficult. But the game takes multiple steps to make the process easier to handle. For one thing, in truth you’re never tasked with uncovering huge numbers of spaces in each square. Typically there will be one square with many separate areas, another with a few, and a couple that have only a couple, if any at all (and even then that’s rare, as you’ll only juggle four panels at once closer to the end of the game). This means you begin to orient your thinking around how the panels you have will interact. If the boy is trapped on a platform in one panel that ends at the frame, can a similar looking section of ground in the second allow him to walk on to explore further? Can I change the temperature on this thermostat to get its needle into the right position, allowing me to use the latter to fill a void somewhere else? It’s in the interest of both accessibility and difficulty; you can’t simply brute force your way to the end because you need to figure out how to put multiple sequences of events into motion in the proper order, but it also helps orient your planning. Getting an interactive series of gears to move is difficult, but figuring it out helps the rest of the puzzle make sense. In addition, after you solve some puzzles, the entire stage will shift to a new story or place, cutting off the older areas and providing new ones.

A section from a fiendishly clever late game sequences that incorporates multiple settings, locations, time periods, mechanics, and environments.

Gorogoa gets a lot out of its conceit on just a mechanical level. Over the course of the two or so hours of play (this one’s short but delectably sweet), the game throws seemingly every idea for a puzzle this structure might be able to do at the player. There are patterns that come together as serpentine ladders, giant gears, moths that hide secret patterns but who have to be pacified with setting up lights, and an interactive railway map. One difficult puzzle involves manually setting up both an object to fall and its destination as it moves in real time, trying to move it between multiple panels that visually connect only when you zoom into certain sections of them. A mid-game sequence that shifts between the boy’s younger and older selves uses a brilliant gimmick of two homemade levers in their rooms, with the panels activating the levers and allowing you access to the other time. Some panels go to an extreme degree and end up showing one fourth of an invisible four squared panel underneath, requiring you to position the panel not just in one way but in relation to whichever additional panels you have on there. And through it all, the game’s handling of this system feels effortless in a way that belies the difficulty of its six-year development.

Like this. This also helps direct the player by limiting what the panel can eventually “do.”

All of this work is tied to art of the highest calibre. The art and animations, all hand drawn by Roberts, are beautiful, easy to read, and carry a masterful use of color and shading (a benefit of the director repeatedly cutting and replacing older work and drawings as his skills improved to keep consistency). It’s a world whose softness is touched by washed out grit, where colors feel deep and intense. While it doesn’t really have many formal similar tropes to it, it’s reminiscent of early woodblock art, or even pottery, art media with which you can more physically interact. The timeline of the vaguely Byzantine city we see is meant to invoke the 20th century – “a brief peace, a lengthy time of war, a period of rebuilding” – but the art comes at it from a distinctly older eye, if that makes any sense. That’s also part of its appeal, that it feels distinctly vintage and just a bit tired. This is a deeply inventive game, but it’s slightly obscured by a quietness from its presentation and friendly, peaceful visuals. There are particular qualities to a lot of classical eastern European and Islamic art, fairly obvious inspirations for Gorogoa, that mesh well with this something of this nature: medleys of gorgeous lines, interwoven patterns, and intimidating vertical architecture. It’s art whose elements often try to make physical and thematic connections, allowing Roberts’ pieces to feature seemingly random bits of clutter that become part of a grand solution. Those patterns, and recurring visual tropes like specific bits of debris or cloth, also ensure that the game always feels stylistically consistent. You may find grandiose lands, but they’re all part of the same space and world.

Many of these environments are literally bridged together via two towers like the ones on the bottom-right.

Look, I get that this writing is weaker than my usual fare, certainly a bit less concrete. The truth is that it’s incredibly hard to really express in writing what makes this game – which, I should be clear, is excellent, and well worth purchasing on your Nintendo Switch – so great and distinct. It’s an exceedingly experiential thing, far more than many other games I’ve played in some time. You can’t really explain how making a bird drop an orb into a plate, only for the orb to be picked up by a young boy, feels. Even other textless games like Virginia aren’t this obtuse, and the progression is as inscrutable as it is brilliant. When Super Smash Bros. creator Masahiro Sakurai presented the Game Designer’s Award to the game at TGS 2018, he played it for the audience, maybe because just describing it is that difficult. Like playing with puzzles boxes or toys, there’s a very tactile sensation to how you poke and prod and try to reach into each image. Despite being only a series of flat images, its spaces are legitimately three dimensional in a way that differs from stuff like Echechrome or Fez. The depth is magical and electrifying, and it contributes significantly to this game working as well as it does.

Sakurai’s presentation at TGS 2018.

And if there is one facet of the game that rivals its gameplay in defying easy description, it’s the plot, such as it is. In the beginning of this entirely wordless game, as you poke around and move the boy forward to collect each of the orbs, you start to see visions of the boy as just a bit older, now in a wheelchair. That pristine Byzantine / Ottoman architecture now has artillery wounds, and the peaceful grassy deck where you find the first orb has debris strewn about it. The further you go in, you see older and older versions of the boy, the city changing with him. As he reads in a barely lit room, bombing raids cause giant bumps. Eventually, you see his adult self reliving a traumatic injury tied to his search for the orbs, and finally you work with him as an elderly man making one last, tired attempt at finding them. But while the game does introduce them from youngest to oldest, their lives, experiences, and appearances all intermingle to the point where it’s often unclear whose memories you’re looking through for answers at at exact moment.

The visual tone in this time period is noticeably darker and rougher.

The narrative through-line isn’t exactly subtle: the boy – or, rather, the old man – is trying to recreate either the city in which he lives or a life he had, something torn apart through violence and war. And to accomplish this, he seeks out this radiant creature he glimpsed as a child, something great and awesome in size and appearance. This journey tracks him through his entire life: as a child injured in a terrible war, a student living in its wake, as a man still suffering its aftereffects amidst a lengthy reconstruction, and finally as an elder coming to grips with his lifelong search. It makes sense that the title and presumed (though never stated) name we might associate with the god-dragon, “gorogoa,” comes from a childhood creature of Roberts’ imagination, a word that stayed with him for years and apparently helped fuel at least some of his creative energy. It’s something you chase and over which you obsess, at times at risk to yourself. Without any words in any form (the better for the story to translate to other languages or perspectives), themes of religion, aging, war, and memory can only be expressed through art and mechanics. It’s a testament to the game’s style and structure that those elements all feel natural, clear, and easy to understand.

It’s not necessarily clear how these four images interacted together in the past, but they’re all interacting now.

Truthfully, trying to make a strict timeline of the plot is not just a fool’s errand, but one that goes against the game’s own goals. It’s about the way our memories and hopes and trauma can all coalesce in a way that doesn’t fully make sense, in this case fragments to an old man attempting to piece together a life that struggles to be easily categorized. However the events occur, the form in which the god-dragon actually exists, are only valuable insofar as they matter to the utterly nondescript main character. Frequently, the boy will have some errant thought in a square bubble. You can dive into it, discover an entire new array of thoughts he’s having – some interconnected, others not – and find whatever images he needs to move him forward. It’s this inner world of his life and perceptions that matter, and like our memories, it’s a tricky thing untied to strict events or actions. Video games have spent decades exploring memories and narrators of varying reliability, but it’s rare to see one take that unreliability and make it not just a feature of gameplay, but the sole mechanic of the game itself. That’s where those tactile puzzle box sensations come into play most strongly, because you start to feel as though you’re sifting and going through your own memories to find just that one thing on the tip of your tongue. Gorogoa takes those feelings – the way we view our childhoods, how our traumas and hopes intermingle in our everyday lives, the way memory can feel just as much like a prison as a paradise – and makes them into actual gameplay.

In the end of the game – after the initial glimpse, the orbs, and only fractured images of the fall that injured the boy – both us and him take that fall to the bottom of a beautiful spire. You’re pressed to look upwards, and both the tower and the city around it are now bombed out. Then you see the slow rebuilding, until by the top the city is reborn in a striking but less personal series of bright whites and grays. After that, the old man finally brings these orbs together in an easy but deeply satisfying final puzzle that remixes challenges, imagery, and ideas from his entire life and the game’s short history. The low key climax is as abstract as it is clear, and it feels deeply triumphant despite having no grand final challenge or bombastic music or heroic speeches. It’s kind and quiet, virtues that mesh with its curiosity and cleverness in a way that feels of its own. That’s maybe the takeaway I have from playing Gorogoa for the second time, that its style and outlook are just as central to its qualities as its brilliant puzzle design and immaculate presentation. I don’t think a game that lacked this perspective could make puzzles this strong or innovative, at the very least not in this way. The game is a marriage of many great ideas and values, the kind of which I started this column to cover. It’s a great example of game design, but it’s also a great example of how that design needs to be powered by the right ethos and perspective.

- Indie World March 3, 2026: Information and Reactions - March 3, 2026

- On Phil - February 26, 2026

- Escape from Ever After | Review - February 17, 2026

I really love Jason Roberts’ work.

Gorogoa is such a wonderful puzzle video game–a transcendental trip through a life told by constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing it.

What an enlightening and fascinating game.

I love the kind of artwork and clues it has because of its gorgeous drawings.

Very mysteriously satisfying.

Thank you so much for sharing this phenomenal game!