In “Center Stage,” Wolfman Jew discusses environments and level design across the games industry. They may be single levels, larger sandboxes, or broader settings. They may be as small as a room and as large as a world. Some may not even be good. But they are all interesting.

Contains mild discussions of the general plot and events of Pentiment, but is written to preserve the game’s mysteries as much as possible.

It’s funny how bad video game architecture is at creating a realistic livable space. A bunch of weird one-off rooms, spaces that have only one entrance; these are important for making environments for players, but not any place you’d ever want to be in. But not Kiersau Abbey. The Bavarian double monastery is set up like an actual building. On the monks’ side, the church connects to a cloister and crypt, the Old Bailey holds the prior’s house and scriptorium, and a large garden brings everything together. You don’t see quite as much of the convent, but it’s set up similarly, and both are tied to the Shrine of St. Moritz. It’s a bit hard to fully get around, but everything connects in a realistic and natural way. Like a real place, not a video game one. A bit disarming, actually.

Image: Source Gaming. The in-game map of the abbey. The menu is filled with potentially useful data, from the layout of the local town to a substantial glossary on relevant terminology.

You spend a decent amount of your time in Pentiment in the abbey. You had better, given that you play someone who works there. Andreas Maler is a somewhat conceited, somewhat flirty, somewhat talented manuscript illustrator in training, a student of a slowly dying art in a town that comes from another time. That would be Tassing, a speck in the Bavarian Alps almost forgotten by the Holy Roman Empire. While the rest of Germany experiences the tumult of the Protestant Reformation, with all the religious revolutions and technologies and wars that came in its stead, Tassing seems quaint, secluded, and utterly normal. Any Catholic village in 1518. But this quiet town of farmers, printers, and monks becomes the setting of an upheaval and conspiracy of its own. After a murder strikes the town, and with no one invested in actually solving it, Andreas becomes a Renaissance-era detective who interrogates witnesses, spies on suspects, and examines bodies. But the deeper he goes into more and more mysteries, the further he seems to get from the truth, all while bodies pile up and chaos threatens to erupt at every turn.

Image: Source Gaming. The first body is found.

Law & Order: Special Benedictine Unit is an indelible pitch for an already fun genre mashup, and Pentiment makes the most of it. The skills you role play Andreas as having are less “powers” and more education, which makes certain avenues of investigation easier. If he studied the occult or spent his Wanderjahre learning French or has a predilection towards loutish violence, those impact the things he can do, the clues he can understand, and the ways he can convince the townsfolk to spill their secrets. So while it’s functionally an adventure game, it’s also a full-on RPG—a knockout courtesy of Obsidian, they of Fallout: New Vegas and Pillars of Eternity. It naturally has incredible writing and characters that power the mystery. And it’s all tied together with stunning graphics that mimic Medieval manuscript art.

Image: Source Gaming. A standard dialogue check. While Pentiment is an adventure game, it’s also very much an RPG whose plot is impacted by your choices. And not always positively; my law background let me make that “pedantic point about corpus delicti,” but that did nothing but worsen my chance of persuading the judge.

These qualities are, on their own, delightful. But what brings them together the most—possibly even more than the art, the game’s biggest selling point—is the setting. Tassing is one of the great video game spaces; it’s a community that feels real, interesting, and full of secrets. And it builds these qualities in a way that makes their discovery exciting.

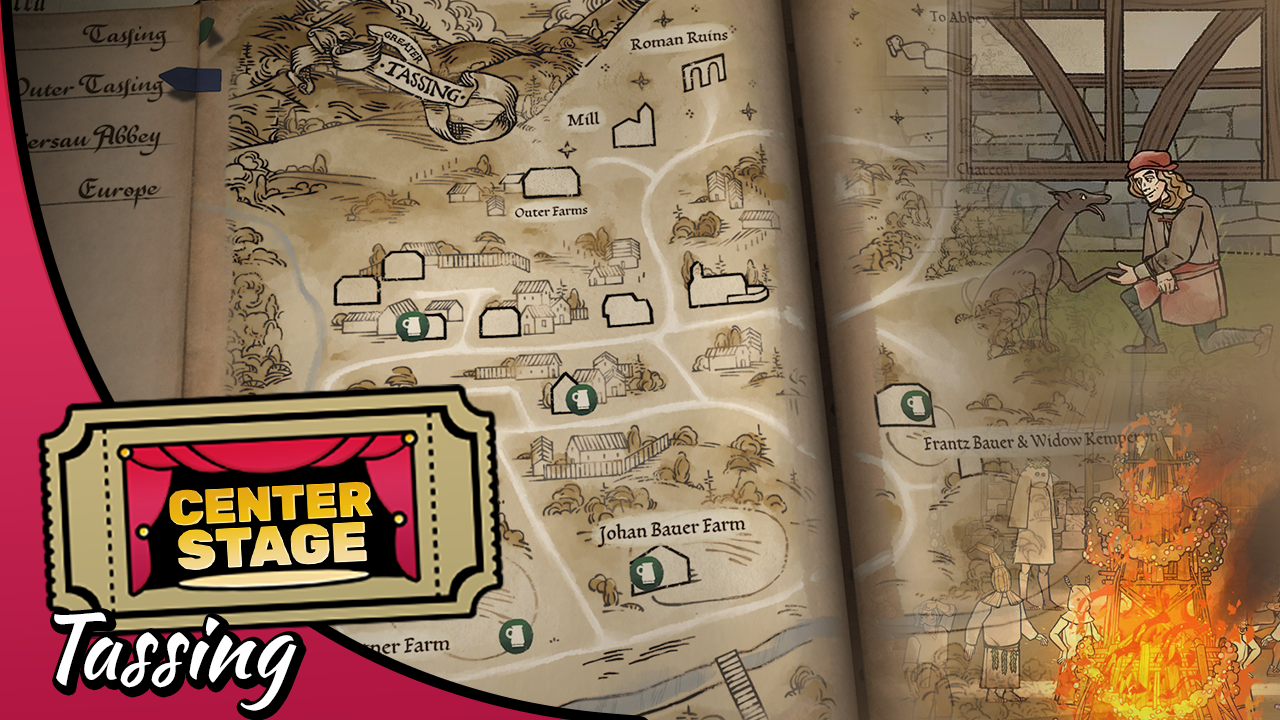

Image: Source Gaming. Early on in the game, when Andreas and the player are still figuring out how to get around town.

On a structural level, the town functions just like the abbey. It’s a collection of small districts and farms that are all interconnected, much like the townsfolk themselves. It’s hard to really get a handle on where everything fits together at first, and especially its community, and you may end up relying on your extensive collection of maps and glossaries. Part of that is that, again, things are connected in a slightly more realistic way than they would be in other games. The farms are tied together, the local church is near the center of things, and side spaces like the forest and Roman salt mine preserve pieces of the town’s pagan history. Tassing is a sea of avenues and bonds that keep folding back in on each other. That’s confusing, but there are ways you can learn. For one thing, gossip is everywhere, so most characters can send you to learn about their neighbors, some of whom you may potentially implicate as a murderer.

Image: Obsidian Entertainment. The game regularly has moments, from weaving mini-games to meals, in which the characters let down their guard. Sometimes this leads to overt clues; sometimes it just adds world-building.

The game has plenty of other ways to help you make mental maps on top of your actual maps. For one thing, like in Fire Emblem: Three Houses you’re encouraged to regularly explore each area. You have to gather clues and information, and you’ll probably want to get as much of the gossip and character development regardless, which means doubling back repeatedly to talk to people. You’ll know the Gertner and Bauer families, whose farms lie to the south. You’ll associate the giant Dutch windmill—the only one in Bavaria, you know!—with its owner, the cruel, abusive, money grubbing Lenhardt Müller. You’ll connect Sister Illuminata to both the scriptorium’s library and the prioress’ house, Smokey and his charcoal burner to the forest, and Father Thomas to the church in town. The more you seek out these characters and learn about them, the more familiar the town and each building becomes. Which is pretty important, given you’re solving a series of killings.

Image: Source Gaming. And when you need help matching faces to names, the game gives you a handy guide you can pull up at any point during dialogue. It does the same for the Medieval terms in the glossary.

Of course, there’s only so much you can do. There is a time limit that’s not too overbearing (idle chatter is free, and it doesn’t play out in real time) but very strict otherwise. The big events that dig up the most clues take a full block of time. Between them and meals, each of which is spent with a different family that may offer up more clues or just enrich the world, you have to decide which avenues to pursue and which people to engage with. Because that’s the biggest part of the role playing; you’re not penalized in any way for finding the “wrong” killer among the three or four you can accuse each time. You just do the best you can with the evidence you find. The story moves on, as do the residents in one way or another. This rewards multiple playthroughs, since you’ll never be able to find every secret or dive into the lives of every person in town. It also allows you to see how your actions alter Tassing, since…

Image: Source Gaming. An older Andreas and his new apprentice Caspar return to Tassing. Characters like Martin have aged and changed—sometimes in shocking ways.

I’ve been dancing around this, because this is a mystery game and preserving the mystery is important, but this needs to be said: the geographical setting of Pentiment may be one tiny village, but its temporal setting is quite a bit larger. Each main act has several years’ distance from each other, meaning that you see the town—and more importantly, its citizenry—age over time. Couples have children who grow into adults, new residents move into town and build it up, and the intricate politics within the abbey change. Certain sections are accessible in certain acts as the town’s landscape changes and outlying areas become ignored. There’s a whole “north town” that only gets constructed years after the first crime, and it’s shocking how big this boring street of two residents feels.

Image: Source Gaming. The violence always beings to spiral outwards somehow, and while Andreas is partially at fault, he’s ultimately as much a rider as an executor.

Naturally, the characters change over the decades in regards to things you both can and can’t affect. The ones who survive Andreas’s amateur investigations are generally relegated to smaller roles, but plenty of the things you do and say affect each new act. Some people’s outlooks and personalities change wildly depending on the things you say and do. Whatever happens, including how everyone else reacts to it, is mostly on your head. This has two important consequences: you always feel like you impacted the town for good and ill, and the town evolves in dramatic ways. Andreas might be a visitor, with his joyless home in Nuremberg hanging over his head, but he fully immerses himself in the community and becomes relevant to its history.

Image: Source Gaming. The population of Tassing only increases so much by Act II, but it feels so much larger. Partially, this is also due to you seeing more communal events, such as Otto Zimmerman’s rebellion against the abbey’s brutal laws and taxation.

However, the things that bring the most change is what’s most outside your control, namely the macro direction of the town itself. For all its bucolic splendor, Tassing is still a deeply poor farming town in an era that was not good to farmers. Between the vagaries of nature, the abuses of its miller and political lordship, and the abbot’s increasingly cruel taxes, the community spends much of its time suffering. When you come back in the second act, it’s shocking to see just how desperate everyone is. The few people you really know, like Claus the printer or layabout thief Martin Bauer or the Brothers and Sisters of the abbey, live with these pains. Maybe one becomes a revolutionary fighting for peasant rights. Maybe one risks the Inquisition by studying gnosticism. The independence the characters have is important from a developmental standpoint (director Josh Sawyer has been open that Obsidian can’t healthily make another game as open-ended or player-directed as New Vegas, and it would futz with the mystery), but it’s also good that they exist beyond Andreas’s thoughtful but clumsy intrusions. This is also true of the town itself, which sways from and in spite of the player.

Image: Source Gaming. Its unassuming nature hides the importance of the town square as a place where events happen, emotions come out, and characters become more amenable to sharing secrets.

This is what makes Tassing so compelling as a perfect and distinct setting for a video game. It’s a space that allows the characters to grow, but it also grows in its own way. It helps make and seed mysteries—literally in a way, as it’s built on Roman and pagan land whose mysterious ruins are strewn about. Most importantly, it supports gameplay in a tangible, active way. It helps you understand the basic mechanics, it constantly teases paths for you to explore, and it lets you acclimate to that incredible art style. The place exists to empower the game, not just the plot, and that makes it feel more real than the townships of far too many RPGs. If the location “that is its own character” is a tired cliché (and it is), this one is the exception to prove the rule.

- Nintendo Direct: Nintendo Switch 2 April 2, 2025: Information and Reactions - April 2, 2025

- Passing the Buck Chapter 14: Super Game Pass 64 - April 1, 2025

- Passing the Buck Chapter 13: Cheers% - March 30, 2025