Thanks to NantenJex for edits.

“Stealth sections suck. They’re not fun, they’re forced; they’re the developers pushing something on you.”

This is not a real quote. It is, however, an accurate portrayal of the prevailing attitude towards the mandatory stealth sequence. It’s a fairly ubiquitous trope of modern action games: a section in which the player character is relieved of their martial talents and must evade capture or death from a passive guard or active pursuer. It changes the pace from action or exploration into something ostensibly tense. The mechanics have to change, too; you’re expected to use cover or avoid the light. In theory, it should be exciting, a moment of disempowerment that makes the retrieval of your abilities all the sweeter.

But many players tend to find these moments the opposite of exciting, and it’s understandable why. When they’re done poorly (as they often are), they’re unpleasant slogs. Your abilities to hide are frustratingly limited, the same tends to count for your movement, and the enemies are all the more painful. A lot of the time, just being seen nets you a Game Over before knocking you back to a far-off save point. And the knocks happen fast when you try to skip over enemies who are so dumb and slow and uninteresting, but whose easy patterns are absolute.

I liked the sneaking portion at the start of The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, but it was a divisive aspect.

Even when these are done well, they’re rarely well received. Fundamentally, stealth operates at such a different level than any other kind of action. Adding it kills – at least for a time – any higher, more energetic pace. If you were playing the game just for that experience, stealth takes you out of that. Having new flavors of interaction can be good and at times necessary for the experience, but ones that are antithetical to the rest of the game can be a hard sell.

Personally, I don’t think there’s anything inherently bad about non-stealth games incorporating stealth or stealth mechanics. It’s a perfectly valid way to explore a relationship between player characters and enemies. And a number of action genres do fit it – horror, for instance. Resident Evil Village would’ve been a lot less without Ethan Winters sneaking through Castle Dimitrescu. But I can’t deny that they’re often poorly implemented, narratively contrived, and bad for pacing.

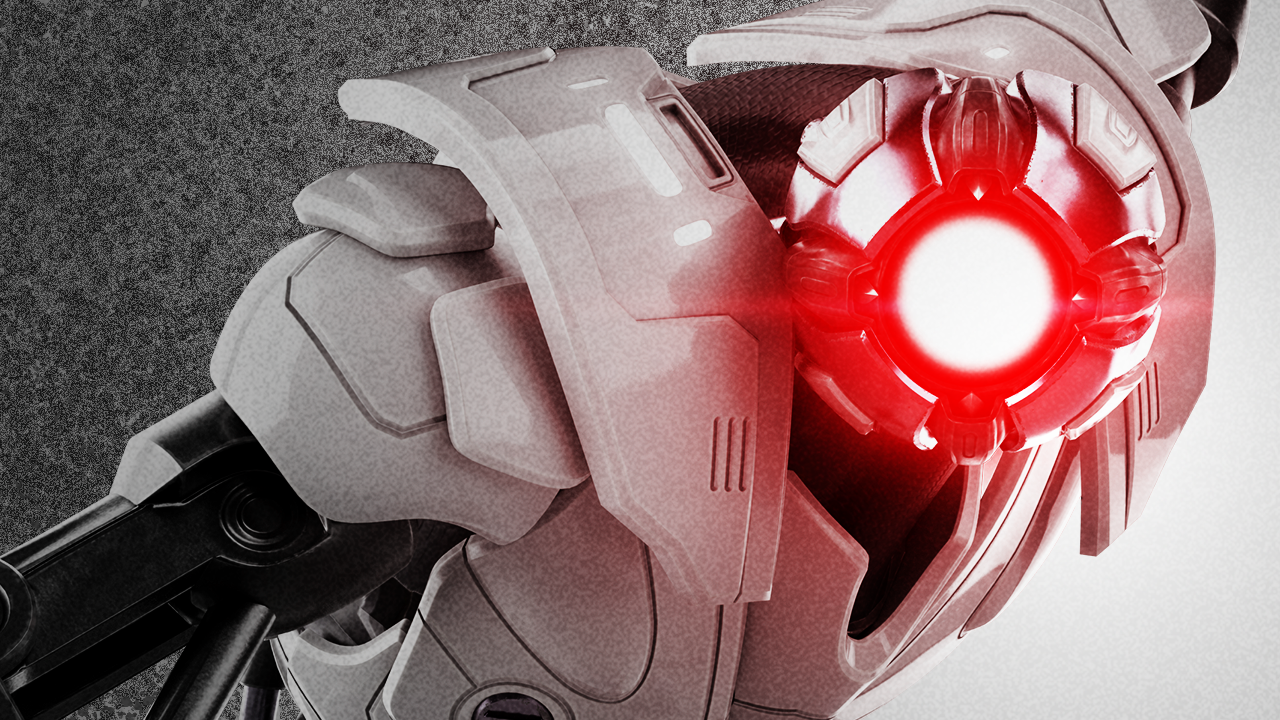

One of the most recent non-stealth games to do this is Nintendo and MercurySteam’s Metroid Dread, which came out this month. Though “non-stealth” might be pushing it slightly; it’s a big part of the experience. Dread did not hide or obfuscate this; the first footage showed Samus Aran, Metroid’s unflappable heroine, being stalked and chased by a creepy robotic assailant. And that’s not a one-time deal; while there’s a larger threat and plenty of bosses, the primary antagonists are the Extraplanetary Multiform Mobile Identifiers, the spidery drones that crawl on the walls and stalk Samus. They can’t be killed – they can’t even be stunned by her many weapons – but they can kill her in one hit. The game sticks them throughout the labyrinthine world of planet ZDR, forcing her to repeatedly infiltrate their areas of purview. And they look like this:

Spooky. True to their design, the machines are scary and exceedingly threatening, which fits the series. From the moment in 1986 when Metroid became one of the first gaming adopters of Ridley Scott’s Alien (and Birdy, with Nicolas Cage, but that’s for another day), the series has had a strong horror aesthetic. Each entry tasks Samus with exploring the caverns and ruins and labs of some terrifying planet, often to hunt down an apex predator – most famously, the Metroids that inspire the title. And the elements of terror and weakness fits the inherent design of the series, where Samus starts off underpowered and has to fight and explore and search to find her powers. That’s the appeal of the genre of “exploration action” (Nintendo’s term, though many prefer the ungainly portmanteau of “Metroidvania”): empowerment by discovery.

Of course, the natural progression inherently conflicts with the sense of terror – things look much less bleak once you’ve gone from five missiles to two hundred – and Metroid has often tried to keep the sense of threat alive. Metroid Prime 2 set half of its map in a painful dark dimension whose very atmosphere sapped your health. Fusion, to which Dread is a direct sequel, featured a viral doppelgänger in Samus’s armor. Zero Mission, a remake of the first game, had an endgame stealth sequence of its own that is very well regarded.

The E.M.M.I. is a very clear evolution of the latter two ideas. Seven of the various locations on Dread’s map have one large section, each the domain of one robot. The moment Samus enters it, she gets stalked by and has to evade it. Each is as fast as Samus, has no trouble climbing the walls and ceilings to chase her, and has sensors that track her sounds. Unlike most stealth sections in non-stealth games (which usually just happen once or twice), this happens repeatedly. And each new area and E.M.M.I. tends to add a new wrinkle, like waterlogged rooms that slow you down or abilities that freeze you. You can block its death strike with a parry, something Dread appropriates from MercurySteam’s Metroid 2 remake Samus Returns, but it’s incredibly difficult to pull off and unreliable for most players.

Seconds before the kill.

This should be a recipe for disaster – enemies you can’t fight, that kill you immediately, and which confront you several times over – but the game takes several precautions to make this less of a trial. In fact, it’s more than that; Dread’s stealth sections are fantastic (if, admittedly, often very tough, and potentially too frequent for some players). And there are a few reasons for that.

Firstly, and most immediately crucially, is that the game has autosaves, and while it’s less generous with them than modern games it’s exceptionally generous for this series. Dread has checkpoints for the rooms right before boss fights and the E.M.M.I. sections, and they’re not true saves (you still always need to go back to the classic Metroid save stations for a permanent save). But that does keep players from having to trek all the way back to a harrowing fight, which is extremely helpful – this is a tough game, and the bosses are closer to Dark Souls territory than any other entry in the franchise. It makes the difficulty much more tolerable.

That’s also aided by the actual spacing of the E.M.M.I. Rooms. The game makes sure that you’ll have to go through them again and again… but not for too long. Every sojourn is quick enough to not dominate the experience, but frequent enough that the E.M.M.I.s are never out of your mind (and in the off chance they are, the map even lists how many are still alive). Think of it like nice bites of stealth, instead of the norm of an action game having one token hiding section before washing its hands of the affair. This arguably goes too far in the opposite direction, since it explicitly delineates when the chase is going to happen. The E.M.M.I. is an incredible enemy, and it is intimidating, but it can’t be truly overwhelming. Which is fine; Metroid Dread is a horror game, just not a survival horror game.

One of the harder parts of this article was trying to explain the nature of the E.M.M.I. movement. Sometimes video (or GIF, here) is the only way to go.

But still… incredible. The robot really is a tremendous creation. Its scuttling, animalistic movement is fantastic, and it contrasts perfectly with that antiseptic, off-white color scheme (several E.M.M.I.s have different color schemes, all of which are quite striking and pretty, but the eggshell color is the most memorable). Metroid has always had an interesting contrast between the man-made and the natural, from its heroine – a woman in a hyper-stylized robot suit – to its snarling beasts and rusted, metallic walls. The E.M.M.I. design is that to an extreme; there’s no blood or guts in them, but they act like there is. It’s a performance built out of excellent animations and fairly good AI. The stalker is arresting, if not so arresting that you’re not immediately looking for a way out.

There’s also the secret in how you actually get past that impenetrable armor: a temporary power-up you get from defeating a mini-boss (specifically one that gets reused for each fight) that lasts just long enough for you to kill an android. But instead of the Omega Cannon being a quick one-shot kill, it only continues the theme. You need to hit the E.M.M.I. twice: burning off its faceplate with a long burst of fire, then blasting it with one charged shot. Samus can only pull off either of these from a distance as the thing creeps towards her, so you still have to keep scrambling away until you find the right position for each hit. It combines the method for victory with the method for survival.

But there is one especially important thing, one thing that ties it all together and makes Metroid Dread as a whole. Which is that Samus runs really, really fast.

One benefit and tweak of this being the first HD Metroid is the consistent wide shot. You know exactly where the E.M.M.I. is – usually close by.

Exploration action is not super well known for movement speed. Castlevania, the other half of “Metroidvania?” No; it’s mostly got a laguid, theatrical pace. The Castlevania spiritual successor Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night? No; it naturally takes cues from its predecessor. Hollow Knight, my favorite game of this genre from the previous decade? No; that one’s pretty slow, too. The mediocre Axiom Verge? Slow. Shantae and the Pirate’s Curse? Slow. And Metroid as a whole, while faster than them, is still in the same boat. Note that I specifically mean movement speed; exploration action is one of the most popular genres in the world of speedrunning, thanks partially to Super Metroid’s place as the gold standard of speedruns (a position Dread is already destined to follow). Samus moves throughout her newest adventure with an agility and facility that is very atypical of this genre – at least, atypical for the vast majority of players, who play on a casual level.

But there’s also a great fluidity to her movement. Her new slide, one of the things Nintendo promoted the most, is revelatory. It allows the game to play with small corridors, something that’s been around since the very first room of the very first Metroid, in new ways (notably, Samus’s classic Morph Ball is hidden for much of the early game to give it space). And it provides an opportunity to build rooms with secret paths Samus can take to avoid an unflappable pursuer. The design makes it relatively easy to bounce into a stride, and although that isn’t always enough in the E.M.M.I. rooms themselves – just because each pursuer is almost impossible to counter – there’s always enough room to keep Samus moving. Combining her run, slide, ledge grab, and wall jump (a Metroid standard that’s never been easier) is very intuitive. And the excellent parry mechanic, expanded from its place in the last game, ensures that the fights have a similar level of kineticism.

This is a huge part of Metroid Dread, and it’s arguably the most important part. The world is massive, more so than most exploration action games. Navigating it takes time; it demands you fight or avoid scores of enemies and repeatedly locks entrances and exists just as it unlocks them. But giving you such great movement makes that much more of a breeze, mollifying the issue some Metroidvania worlds have of being too big for their movement speed.

The current world record for Any% as of the night before this publication. Naturally, Dread speedrunning makes extensive use of these moves.

But within the E.M.M.I. Rooms themselves, this speed turns the typical idea of a stealth sequence on its head. In virtually every iteration of video game stealth as a concept, you’re forced to slow down. That’s true in stealth games like Metal Gear or Hitman, and it’s all the truer in action games that appropriate the mechanics. In virtually every game of the latter category, you have to sneak or crawl or tiptoe behind guards who always walk the same slow, methodical patterns. That’s a big part of why these sequences are so disliked; they kill the pace in favor of bland pattern recognition. But in Dread, the stealth sequences are the times where you have to be at your fastest and most improvisational. The E.M.M.I. is as fast as you, has free reign of its space, has patterns that are hard to manipulate, can go through vents you can’t, and actively homes in on you. You cannot outsmart it, not forever. So you outrun it.

There is a way to hide from the E.M.M.I., a cloaking move that turns Samus invisible, but it’s limited by design. It only lasts a short few seconds, keeping up past that point eats at Samus’s health, and it doesn’t work if the E.M.M.I. touches her. It is a last resort you can’t rely on regularly, so naturally a later robot has advanced sensory powers that force you to rely on it – the Nintendo standard of eventually throwing you to the deep end.

The dynamic nature of this relationship between human hunter and machine hunter is representative of a lot of Metroid Dread, which attempts to add a great deal of material that’s not standard in exploration action. Alongside permanently closing some doors (thus forcing you to find alternate paths), it features a number of set pieces that aren’t exactly genre standard. One forces Samus to escape a trapped space with death nipping at her heel, something not at all unknown for Metroid but done here with more action movie flair. At one point, much of the world becomes dangerously inhospitable, forcing you to find new paths to set the conditions right. Later in the game, most of the weak or benign enemies you’ve encountered for hours are replaced by more powerful and hostile monsters – something reminiscent of Hollow Knight’s spooky Infected Crossroads.

I was shocked when this fight started. It was like fighting Ornstein all over again.

In fact, you can see quite a bit of Team Cherry’s 2017 classic in this game, especially in the Souls-esque duels against militant spearmen. But to a broader point, the game feels of a piece with modern exploration action – and action as a whole. The autosaves are the kind of modern convenience that Super Metroid lacked. The tactile parry, something at odds with Metroid’s historical preference for safe distances, feels closer to high octane brawlers. And the set pieces, from escape sequences to quicktime events, are the kind you expect from cinematic, linear adventures. It’s clear the staff had plenty of inspiration, something Nintendo games try to obfuscate just a bit.

It goes oft-mentioned during discussions of the game, but Dread has a long history. Alongside being the first fully new Metroid mainline entry since 2002 (something Nintendo loves to mention), production also started all the way back in 2005 before stopping. That’d have been for the Nintendo DS, and it’s easy to imagine the lovable handheld just sighing and shutting down at the prospect of having to implement a single E.M.M.I. encounter. So this is a very old game, and from an old series (Metroid had its 35th birthday two months ago), but it doesn’t feel that way. Dread could have easily felt like a relic in a landscape full of imaginative, modern Metroidvanias – the genre of choice for a disproportionately large number of indie games. Instead, it feels vital and new, partially because it recognizes the landscape Super Metroid influenced. It’s willing to play with the old and accept the new.

And few things in Metroid Dread feel newer – or at least less standardized – than these chases between Samus and her android aggressors. They don’t feel quite like a lot of things, but they especially don’t feel anything like Metroid or anything like a typical stealth section. They’re energetic where bad stealth feels lethargic. They force Samus to move in ways that are rare for her outside of high level speedrunning. This movement and energy are so deeply compelling, and while I died a lot in those barely living rooms, I still loved figuring out each puzzle and smiled whenever I got one past that darned robot. The entire process combines multiple things I love: climactic fights, fast movement as a standard and not a reward, encounters that make you rely on plenty of skills, and good character design. And it uses them to better this weird mechanical trope that can be such a pain at the worst of times.

It’s clear Nintendo saw the E.M.M.I. as a valuable point of marketing; it got its own amiibo. A quite nice looking one at that.

Dread does, of course, have more things worth discussing. There’s its limited but intriguing plot that prioritizes subtler environmental storytelling (something that was, apparently, the secondary but happy result of COVID-19 conditions jettisoning a heavier narrative). The music is also great, going more into weird and spooky ambiance than the rocking action themes for which Metroid is well known. Then there’s the high difficulty for its bosses, which is perhaps excessive at times. And I don’t feel comfortable writing about the game without mentioning the controversies of MercurySteam, both in its excluding some of its former workers from the credits and in years-long rumors of poor treatment of its staff.

But the E.M.M.I. really grabbed me from the start, even before playing the game. It’s such an abnormal character design for this industry, and so creepy and intriguing. And the points in which it appears live up to that. It’s not just a way to make a “good stealth section;” it creates something that totally unique. Which is good at the best of times, but great when it comes from the ninth entry in an old series (with a six-entry spin-off) and a maligned mechanical trope. Fighting each machine made me feel what every instance of bad mandatory stealth routinely does not: alive.

- Passing the Buck Chapter 14: Super Game Pass 64 - April 1, 2025

- Passing the Buck Chapter 13: Cheers% - March 30, 2025

- Nintendo Direct March 27, 2025: Information and Reactions - March 27, 2025